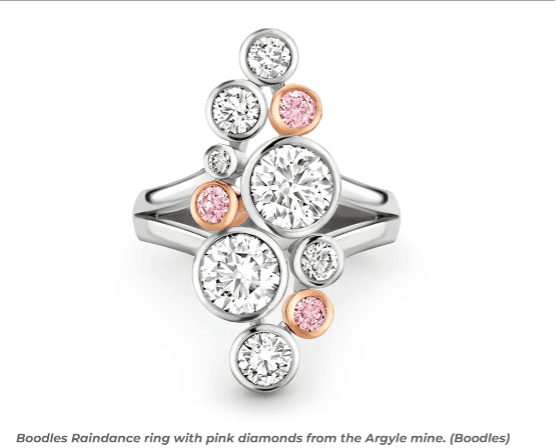

Last year, British jeweler Boodles inked a deal with Rio Tinto to gain direct access to diamonds from the latter’s Diavik mine in Canada, as well as to the remaining pink diamonds from the miner’s now-closed Argyle deposit in Australia. The Diavik diamonds now appear across Boodles’s collections, while the pink diamonds are integral to its Raindance collection, now in its 25th year.

Boodles is not the only jeweler taking a more direct approach to its diamond supply. In Paris, designer Valerie Messika takes a personal interest in acquiring diamonds from one of the Namibia cutting and polishing facilities belonging to her father, diamantaire André Messika. He, meanwhile, has just signed a deal with Burgundy Diamond Mines to bring the Ekati deposit’s yellow diamonds from Canada to prestigious jewelry maisons, complete with Burgundy’s certificate of origin to ensure each diamond’s provenance.

The increasing demand for transparency when it comes to diamond origins and production has persuaded jewelers to form partnerships with mines to provide that clarity. Following a 2018 Human Rights Watch report on the hidden ethical costs of making jewelry, “there was a bit of a pressgang operation against retailers to effect change down the supply chain,” recalls Jody Wainwright, managing director and gem-buyer for Boodles. “Nasty as it was, it was probably quite a good thing.”

African connections

For its own part, the UK jeweler has a strong commitment to sustainable practices. Among other things, it has been partnering with the Cullinan mine in South Africa since 2015.

“We’ve always had a program of partnerships, because it is nice for us to tell the story that this diamond came from the Cullinan mine and was recovered on such and such a date,” Wainwright says. It’s a solid start to marking a diamond jewel’s chain of custody.

Boodles’s 2022 Peace of Mined collection led to a conversation with Rio Tinto in which the miner proposed the Diavik rough-diamond arrangement, along with a supply of polished pinks as a bonus. The Diavik deal will be in place until goods from the Canadian mine, which is set to close next year, run out. Rio Tinto’s comprehensive green policy and partnership with Indigenous communities include a commitment to return the land to a pristine state once the mine ceases operations.

Meanwhile, family-run New York jeweler Kwiat, which specializes in diamond rings for the bridal market, launched its Mine to Shine program a couple of years ago. The program traces a diamond’s journey from mine of origin through the various stages of the pipeline, culminating in its sale to the customer as an engagement ring.

“It is not just the origin and the cutting process; it is the social impact of the diamond along the way, and we have found that customers really want to know more,” says CEO Greg Kwiat. “They like to learn. It is a deeper level of engagement, and in order to do this, we have a very tight supply relationship and clear chain of custody tracking the process from the mine to the store.”

The jeweler has focused on Botswana as a primary source, going through the state-owned Okavango Diamond Company. It also sources from South Africa and Namibia via De Beers channels. The program involves photographing the stone’s journey at every step, and while this is an investment of time, energy and resources, “it is important as a premium luxury brand to have differentiation, to demonstrate clarity,” says Kwiat.

Customer feedback “has certainly driven us to be better and improve, but when it comes to transparency, this has only been possible in the last few years,” he adds. “Ten years ago, transparency of origin wasn’t possible.”

On a smaller scale

Many independent jewelers lack the scale or power to sign deals with mining companies but still want to ensure that their diamonds come from sustainable sources.

Brands such as Elhanati, Aymer Maria, and Dries Criel have had to find alternative solutions. Dries Criel’s eponymous founder, for example, buys his larger diamonds from manufacturer HB Antwerp, which sources its rough from Lucara Diamond Corp.’s Karowe mine in Botswana.

“For my solitaire-diamond-buying customers, it is extremely important to be able to follow the entire process of the diamond,” says the Belgium-based Criel. “Not only do they value transparency, [they] appreciate the journey and the work toward a timeless heirloom.”

Antwerp-based Nicholas Moltke has been helping independent jewelers source diamonds on a smaller scale through his Botswanamark branded-diamond company. Having worked for De Beers in Botswana for five years, he saw an opportunity seven years ago to provide retailers, brands and jewelers with “tools so they could demonstrate how diamonds were traced and [show their] confidence in the original stone.” This would also let them “tell their clients about what good these diamonds do, how they really have a positive impact and make a difference for people, contrary to what the lab-grown industry was saying and perhaps what people believe today.”

His vision, he explains, was to aid “small jewelers who don’t have the resources and the abilities to secure a big mine collaboration” in setting up their own traceability mechanisms.

Moltke works with Debswana — the joint venture between De Beers and the Botswana government — to source diamonds from three Botswana mines. He uses iTraceiT blockchain technology and well-trusted partners to follow the stones’ cutting and polishing journeys, focusing on sizes from 0.70 to 5 carats as well as melee.

Jewelers “see the stones that are available [online], and from that, pick and choose,” he explains. “They can see the pricing and a video of the stone, and certification that they can show to a customer. [They can also] make an order,” even for two or three individual diamonds — there is no minimum.

Satisfied customers

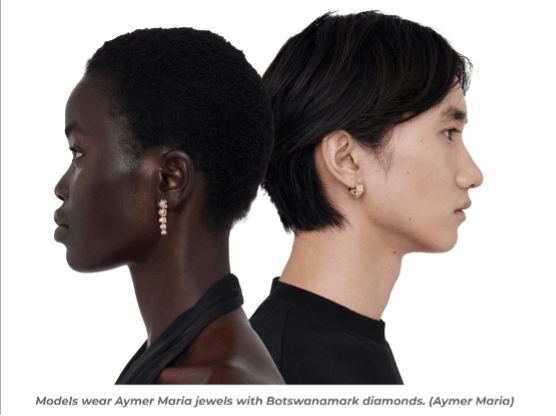

Ruth Aymer Marten uses Botswanamark for her London-based Aymer Maria brand. Her company’s first diamond collection, Malian, features baguette cuts, and her next will have trilliants.

“I show [Moltke] the designs and type of diamonds I am looking for, and he will source them for me,” explains Marten. “I am West African and Sierra Leonean, and the story of blood diamonds is very personal to me. So it is important that I should be able to trade with the surety that there has been no harm done.”

Another of Botswanamark’s clients is Orit Elhanati of the eponymous Danish brand. “We have a good idea of the carat sizes we need every month,” she says. “Besides full transparency, [Botswanamark] also provides the close contact we need.”

She appreciates that Moltke knows “the community around the diamond industry in Botswana well. This knowledge, together with blockchain knowledge and [Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC)] membership, makes it my preferred partner for natural diamonds.”

Responsible-sourcing initiatives like these “give brands the opportunity to bring together their values [to create] deeper storytelling [for] consumers,” says Raluca Anghel, head of external affairs and industry relations at the Natural Diamond Council (NDC). “Natural diamonds have a meaningful impact, especially in diamond-producing countries, and the story of how they make their way to us is incredibly powerful and worth shedding light on.”