Recently, the natural-diamond trade began a wave of pushbacks against lab-grown, a move many saw as long overdue. Amid the stinging jabs and outright mudslinging, as some called a few of the freshly minted marketing campaigns from industry groups, a more subtle approach was taking place somewhat in the shadows.

In June, Belgian lab HRD Antwerp said it would no longer issue certificates for loose synthetic diamonds. The move, it explained, was a way to create a clear distinction between lab-grown and mined, and to underscore HRD’s commitment to bolstering the natural-diamond industry. The decision from the company, a subsidiary of the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), came shortly after the AWDC filled a gumball machine with lab-grown diamonds in an effort to demonstrate their lack of value.

The same month, the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) announced it would still grade lab-grown, but it would migrate its terminology away from the 4Cs and instead only designate the stones as “premium” or “standard.” The new characterization would help consumers understand the differences between natural and synthetics, GIA explained.

“The GIA diamond-grading system was created to recognize the continuum of rarity of natural diamonds from the most rare to the least rare; that does not apply to laboratory-grown diamonds,” the GIA told Rapaport News. “We recognize that the use of [it] for laboratory-grown diamonds may have been misunderstood by retailers and consumers, leading to confusion.”

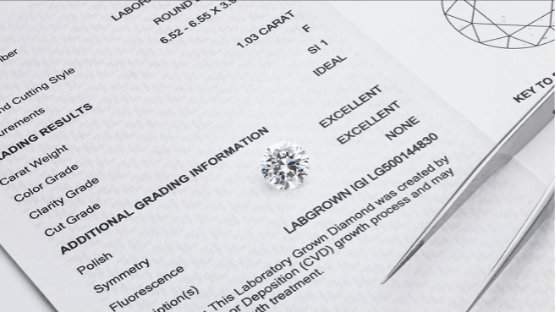

The commotion caused the International Gemological Institute (IGI) to issue a press release in response, which appeared to say nothing at all. The lab reiterated its intention to continue as per the status quo –grading both natural and lab-grown using the 4Cs. While some might wonder why IGI felt the need to basically say “Hi, nothing has changed,” the lab understood the nuances of both HRD’s and GIA’s announcements — to highlight the differences between the value of natural and synthetics, and to hope demand would follow suit. Considering lab-grown grading comprises more than half of IGI’s business, maintaining demand and desire for the product was of primary concern.

Sudden switch

The latest declaration begs the question: why did the GIA originally switch to 4Cs grading for synthetics in the first place, notes diamond-industry consultant Avi Krawitz. He believes the move was in answer to industry pressure from large manufacturers who had moved into lab-grown. However, the pendulum swinging a bit too far in one direction upset the natural side, and the pressure is on to correct the balance.

“The GIA has what to answer for because synthetics gained market share, in retail stores and from jewelers pushing the products to their customers,” Krawitz said. “Jewelers told their customers about this alternative product, and they were able to do so with the GIA report, which completely legitimized it.”

The large portion of market share lab-grown did manage to grab was something most never saw coming; nor did they predict its effect on the natural market. Now many in the industry have realized that they need to differentiate between the two, asserts Krawitz, and the grading element feeds into that sentiment.

“The GIA move was a message to the trade and that echoed what the industry was feeling,” he says. “I think that the next stage will be moving from a grading lab report to a quality assurance thing. I am quite confident this is just the first move toward that direction.”

Making a difference

How will the walk back on grading affect lab-grown? Will the lack of report, or the lower-grade certification, affect consumer demand? Krawitz believes it may.

“I think what the report does for the trade, for the dealer and jeweler that’s selling the diamond, in maintaining the 4Cs, and maintaining the same method of grading to natural, it sort of legitimizes the product, and so they are able to sell to consumers in the way that they have — as a comparative product to natural,” he says. “And that would resonate with consumers. They want to spend less but they still want to feel like they are buying a diamond. So it kind of gives the product that aura.”

Industry analyst Paul Zimnisky agrees to some extent. “I think in a lot of cases these reports have been primarily used as a marketing tool for retailers trying to imply an inherent rarity to the product that doesn’t really exist,” he states. Yet he also thinks getting around it is relatively easy, noting that in lieu of HRD or GIA reports, retailers will probably go with whatever certificate is on the market. Which lab it comes from won’t matter, he continues, because most consumers want two things: an eye-clean diamond, and to save money. Since that can be said of pretty much all lab-grown these days, the report is merely an accessory that won’t make or break the sale, unlike for natural, Zimnisky says.

Diamond consultant Edahn Golan sees the potential for two separate outcomes, depending on how jewelers frame lab-grown when selling.

“It’s hard to find today lower color or clarity lab-grown…and growers are moving quickly toward a D-flawless product,” he says. “As this process is taking place and price differentiation is disappearing, the finer nuances of grading are less impactful in determining price. However, GIA is regarded as the industry standard by both the trade and consumers. I’m not sure what will happen, but it’s mostly in the hands of retailers. If they sell lab-grown as a low-cost standard product for their beauty, the importance of the grading report will likely diminish.”

However, if they also see it as a commodity, he adds, “they will need to provide a grading report to back up their claim. In that case, retailers that feel it’s important for their consumers will have to make sure to have IGI-graded goods on hand.”